TIMELINE

Early Helladic and Middle Helladic period: The first inhabitants of the Hills

The first indications of human presence on the Hills are traced to the east of the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos) between 3200 and 2000 B.C. The existence of a group of dwellings as well as a large grave, dated between 2000 and 1600 B.C., are documented in the same area. The archaeological finds are scattered and fragmented, therefore the wider area of the Hills remains largely unexplored in terms of archaeological research. It is possible that the modern structures have covered to a great extent the pre-historic remains, or may have even destroyed them.

Selected bibliography:

Immerwahr 1971, 97–98; Pantelidou 1975, 45–141; Pantelidou-Gofa 1996.

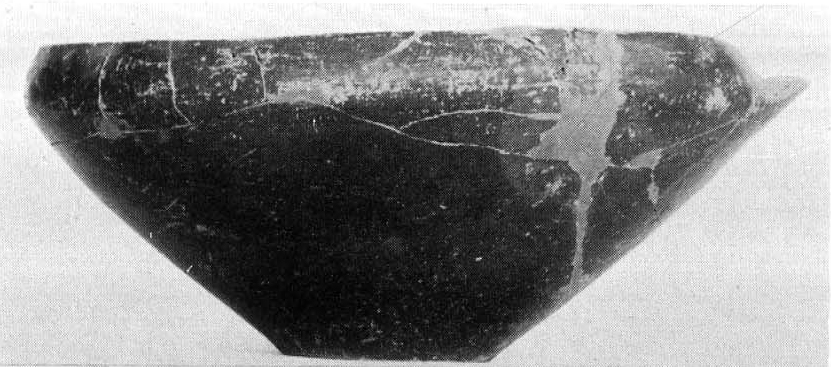

One-handled phiale from a grave of the Middle Helladic period, found in the plot surrounded by 31 Garibaldi, Sofroniskou and Fainaretis Streets.

(Source: Pantelidou 1975, pl. 1β)

Mycenaean period: Scattered traces of residential and burial land use

A rich chamber tomb (1500–1400 B.C.), unfortunately looted, was probably part of a cemetery to the east of the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos); it contained golden ornaments and a piece of jewellery. The old locations continue to be inhabited in subsequent years (1400–1100 B.C.), until a new cemetery is being formed to the west of the Acropolis, on the foot of the Hill of the Nymphs, and another one to the south on the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos), next to a curve of Ilissos river, where Dimitrakopoulou street ends today.

Selected bibliography:

Immerwahr 1971, 98, 178–181; Pantelidou 1975, 45–141; Mountjoy 1995, 14–15, 17, 32–36, 46, 61; Pantelidou-Gofa 1996.

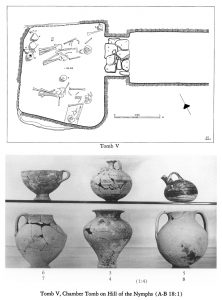

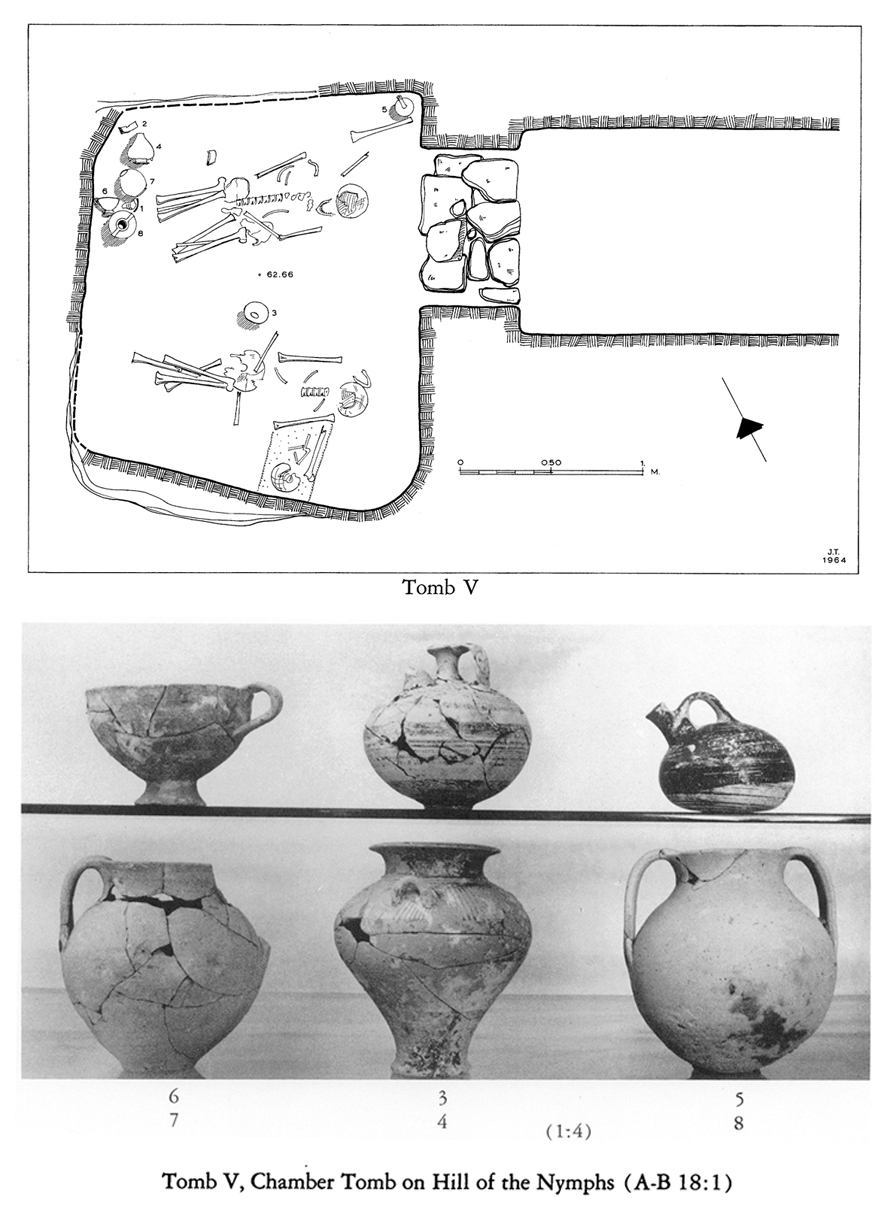

Plan of a Mycenaean chamber tomb and finds of the Mycenaean cemetery at the slope to the northeast of the Hill of the Nymphs.

(Source: Immerwahr 1971, pls. 37–38, 82)

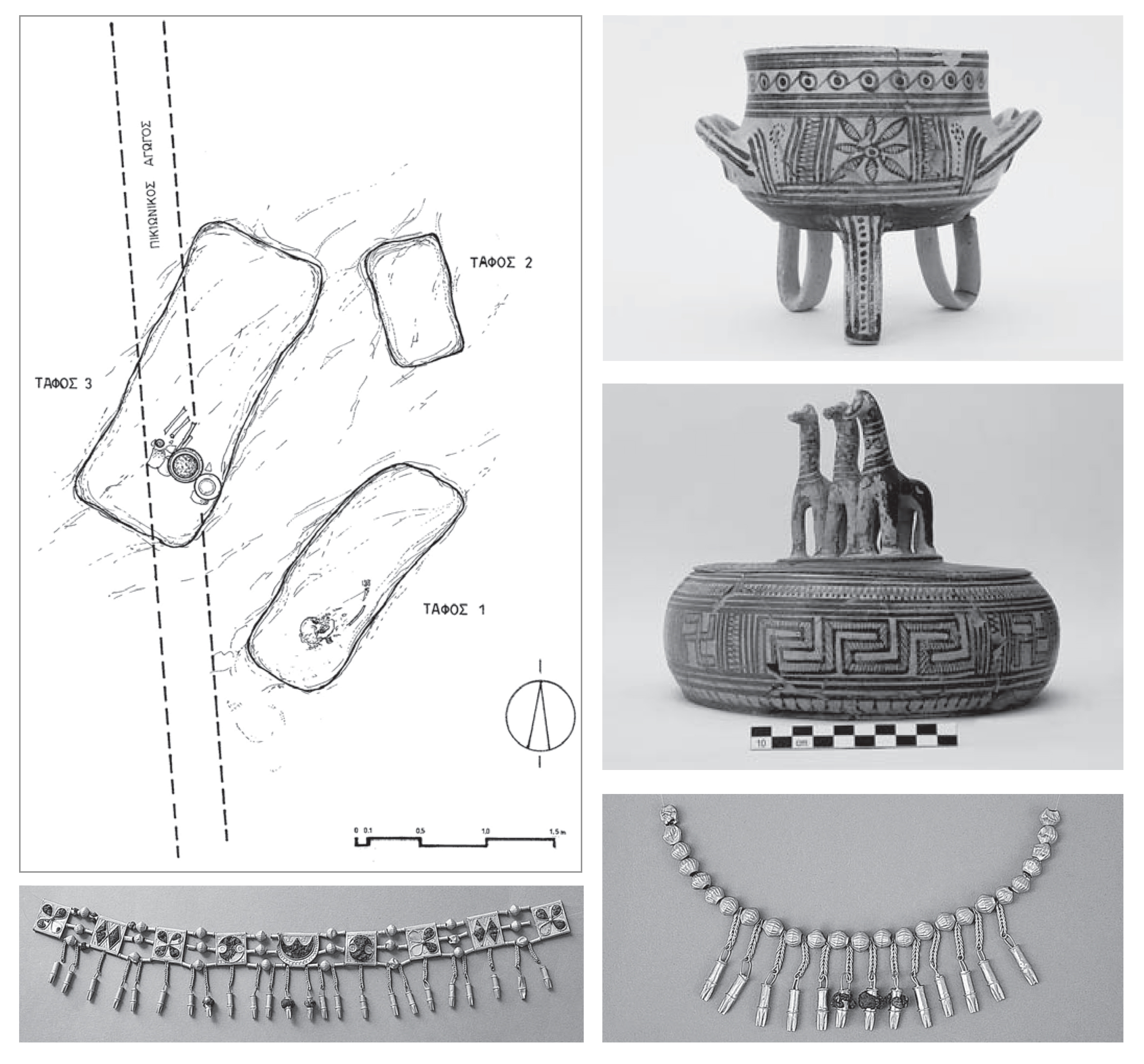

Geometric period: Traces of habitation and extended burial areas

At the Pnyx excavations very few pottery fragments of the Geometric period were found, denoting though human presence on the Hills during this time. Few Geometric finds were also located at excavations in the area of the church of Agios Demetrios Loumbardiaris. However, recent excavations at the eastern slopes of the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos) revealed a cluster of three graves of the Geometric times containing notable findings. It is possible these graves are part of a cemetery that expanded in the area during this period.

Selected bibliography:

Poulou 2013, 231–246.

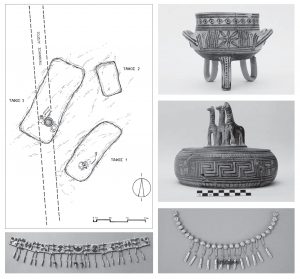

Plan of graves and important finds from the Geometric cemetery excavated at the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos): cosmetics boxes and jewellery.

(Source: Poulou 2013, fig. 2, 6a, 6c, 7b)

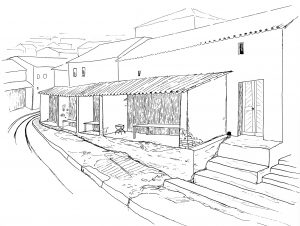

Archaic period: Dense habitation, public buildings and sanctuaries

Upon the rocky lands of the Hills two important demes (districts) develop in antiquity: Melite and Koile. In the deep hollow between the Pnyx and the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos) the “Koile road” takes shape, known to us by Herodotos; a significant commercial and strategic road connecting the city with its port, Piraeus. Upon the Hill of the Pnyx convened the Assembly of the people, whereas the shrine of the Nymphs on the homonymous Hill and the shrine of Zeus at the northeastern plateau of Agia Marina are also founded.

Selected bibliography:

Travlos 1971, 466–476 (Pnyx), 569–572 (sanctuary of Zeus Hypsistos); Forsén and Stanton 1996; Dakoura-Vogiatzoglou 2013, 195–196.

Depiction of the ancient Koile road amidst its residential environment.

(Source: Lauter 1982, 46, fig. 3)

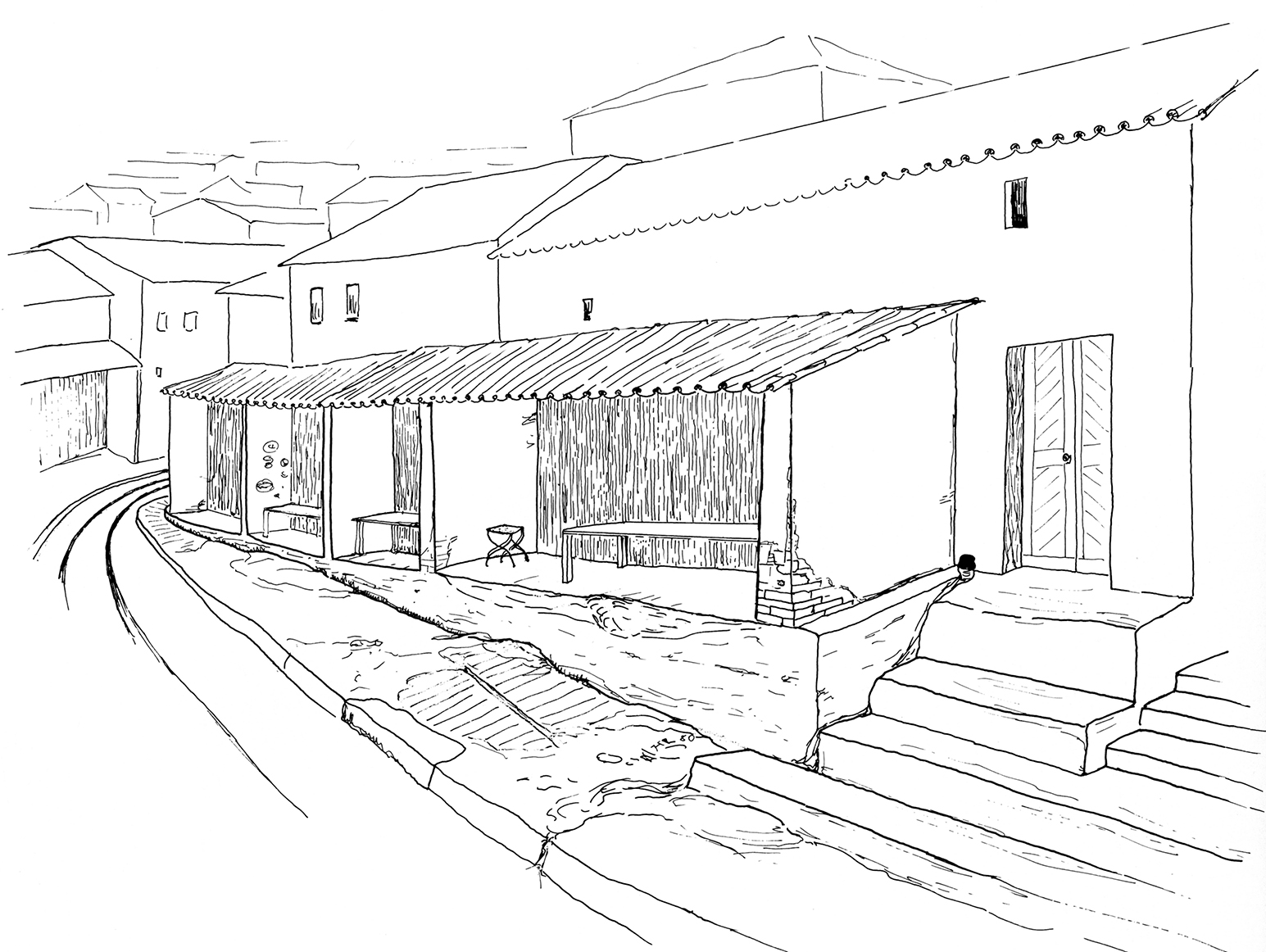

Classical period: Rock-cut houses on heights and slopes

In 479/8 B.C., the demes of Koile and Melite are protected by the Themistoklean wall and manifest significant residential growth during the 5th and 4th centuries B.C. On this stretch of land habitation had an advantage: not a single raindrop could be trapped on the rocky soil. Today, remnants of residential areas are evident on the large plateau to the west of the Hill of the Pnyx, whereas two-storey houses have been found northern to the sanctuary of Pan, on Apostolou Pavlou Street, as well as on the eastern slope of the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos). It is believed that no space suitable for the construction of houses was left unexploited.

Selected bibliography:

Judeich 1931, 124–144; Lauter–Bufe and Lauter 1971, 109–124.

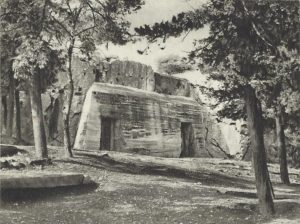

Part of a two-storey house of the Classical age, on the eastern slope of the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos), cut into the rock; known as “Prison of Socrates”. Photograph by Petros Moraitis (1835?–1905).

(Source: gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France)

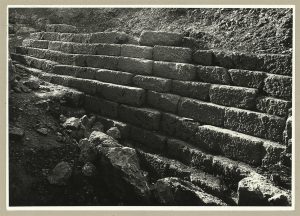

New location of the bema of the Pnyx

The area of the Pnyx is reshaped by the construction of a monumental semi-circular retaining wall and from then on the convening citizens have their backs turned against the city. Upon the Hill, begins the erection of two stoas that would delimit the area to the south of the Assembly Place. It seems as though their construction remained incomplete, whereas a while later the assembly of the Athenians was transferred to the theatre of Dionysos.

Selected bibliography:

Kourouniotes and Thompson 1932, 90-217; Travlos 1971, 466-476.

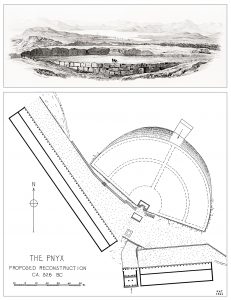

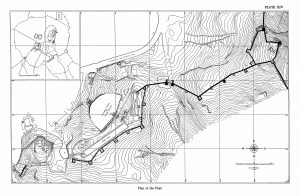

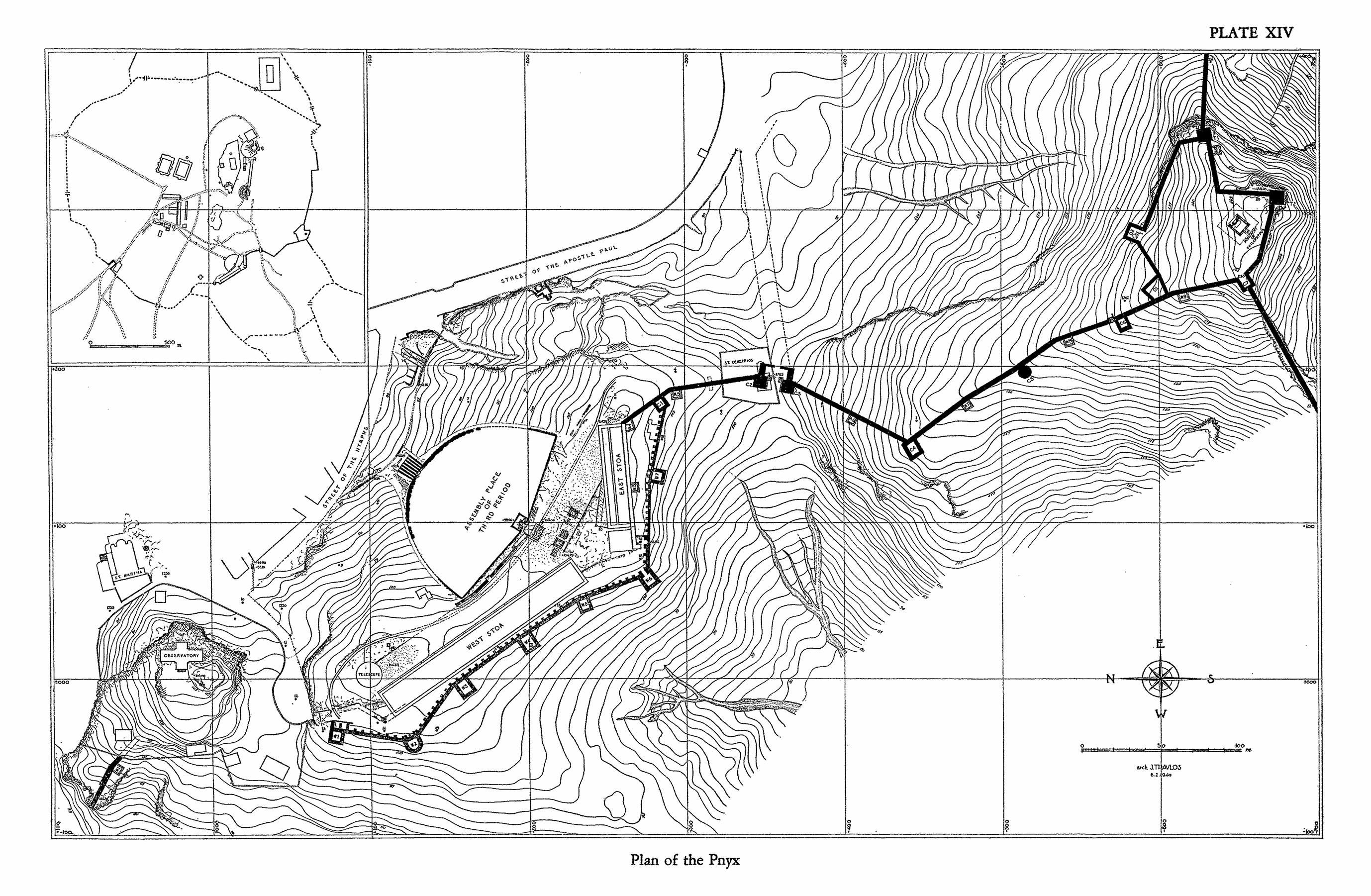

Top: View from the Pnyx overlooking Piraeus. Drawing by the British architect and archaeologist Charles Cockerell, taken from the series “The Antiquities of Athens”, vol. V (1830).

(Source: The National Library of Greece, Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation, from the website www.travelogues.gr of the Aikaterini Laskaridi Foundation)

Bottom: Reconstruction of the Pnyx in a drawing during the 3rd building phase, circa 330 B.C. The excavations in the area of the Pnyx were undertaken by H. A. Thompson and R. L. Scranton in cooperation with K. Kourouniotes, in 1930–37.

(Source: Thompson and Scranton, 1943, 290)

The western slopes of the Hills outside the city’s enceinte

Demetrios Poliorketes (Besieger) installed a garrison at a fortress on the top of the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos), dubbed as Macedonian fortress (294 B.C.), whereas almost at the same time the Athenians construct along the ridge the so-called, 850-metre-long diateichisma that reduces considerably the perimeter of the walls; the defence at the steep Hill of the Pnyx is also reinforced in the early 2nd c. B.C. Gradually, the once-upon-a-time inhabited western section of the Hills is transformed into a cemetery that remains in use from the 3rd c. B.C. until the 3rd c. A.D. A total of 175 unlooted graves have been excavated.

Selected bibliography:

Thompson and Scranton 1943, 301–362; Dakoura-Vogiatzoglou 2008, 258–259.

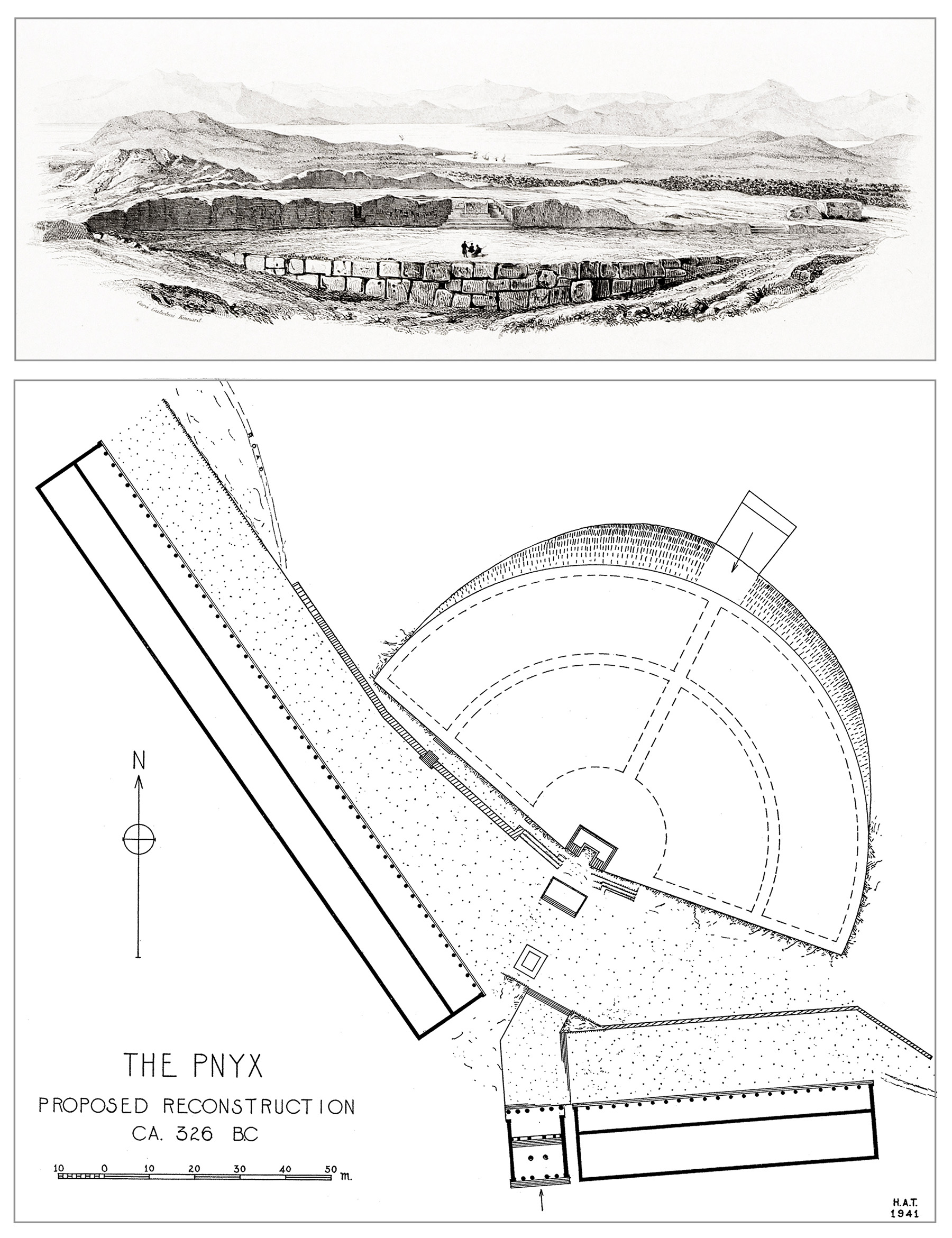

Topographic drawing of the Compartment Wall (diateichisma) on the Western Hills of Athens.

(Source: Thompson and Scranton 1943, 284–285)

Early Imperial period: The sanctuary of Zeus Hypsistos

Under the orders of emperor Augustus (31 B.C.–A.D. 181) the monumental altar of Zeus Agoraios, patron of the orators, is being transferred from the Pnyx to the Agora, in front of the Metroon (Registry), and the operation of the Ekklesia (the Assembly Place of the people) is interrupted. Towards the end of the 1st century A.D. and close to the bema of the Pnyx, the sanctuary of Zeus Hypsistos is founded with niches cut in the face of the scrap; it would be in use for another 200 years.

Selected bibliography:

Kourouniotes and Thompson 1932, 160–162; Camp 1986, 186; Forsén 1996, 49–51.

Rock-cut niches next to the bema of the Pnyx, a spot for leaving dedications to Zeus Hypsistos who was considered a healer god. Photograph taken in 1930.

(Source: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives, Archaeological Photographic Collection, no AP0348)

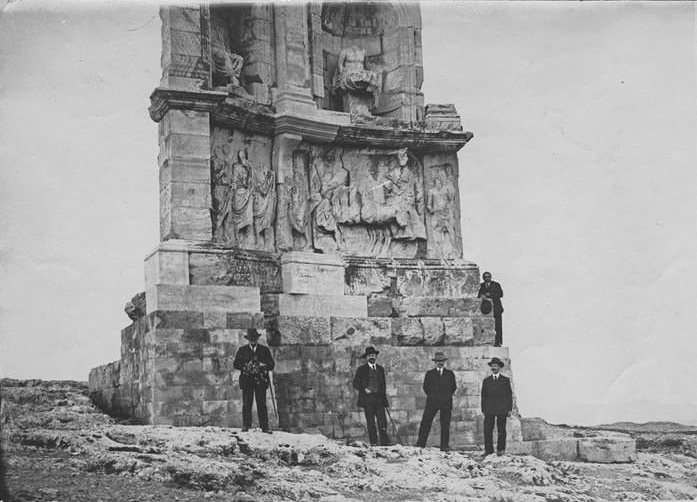

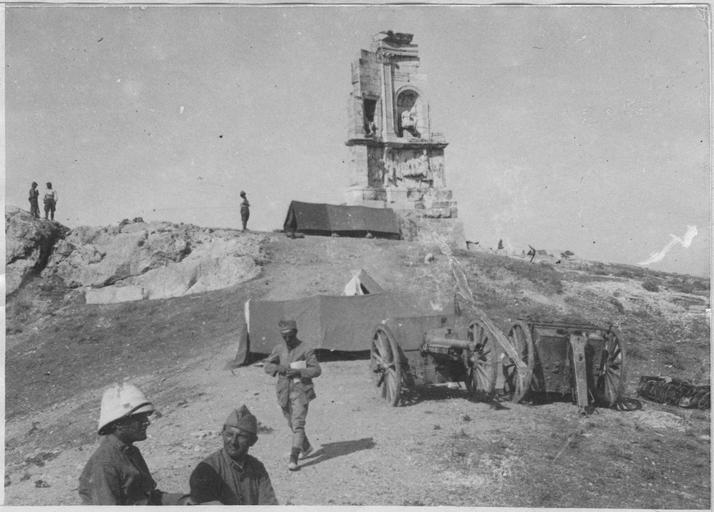

Construction of the Monument of Philopappos

The funerary monument dominates at the top of the Hill of the Muses, that, along with its pedestal, rises approximately 13 meters high; erected in honour of the great benefactor of the city of Athens, Gaius Julius Antiochus Epiphanes Philopappos, prince of the Commagene dynasty (area of modern Syria). It is believed that architectural parts of the monument’s superstructure were used for the construction of the mosque’s minaret built on the Parthenon.

Selected bibliography:

Santangelo 1947, 153–253; Travlos 1960, 122–123.

The monument of Philopappos, “pilgrimage” for those visiting Athens. Photograph taken in 1917.

(Source: Ministère de la Culture (France) – Médiathèque de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine – Diffusion RMN, APOR094226)

Roman citizens settling on the Hills

The small rock-cut shrine bearing the relief representation of Pan, to the northeast of the Hill of the Pnyx, is transformed and constitutes part of a luxurious residential complex; it has undergone consecutive repairs from the 2nd until the 5th centuries A.D. and is definitely abandoned during Justinian’s time. The complex is built upon cuttings of the Classical period and was revealed in excavation trenches within the scope of the project for the Unification of Archaeological Sites.

Selected bibliography:

Dakoura-Vogiatzoglou 2008, 250–254.

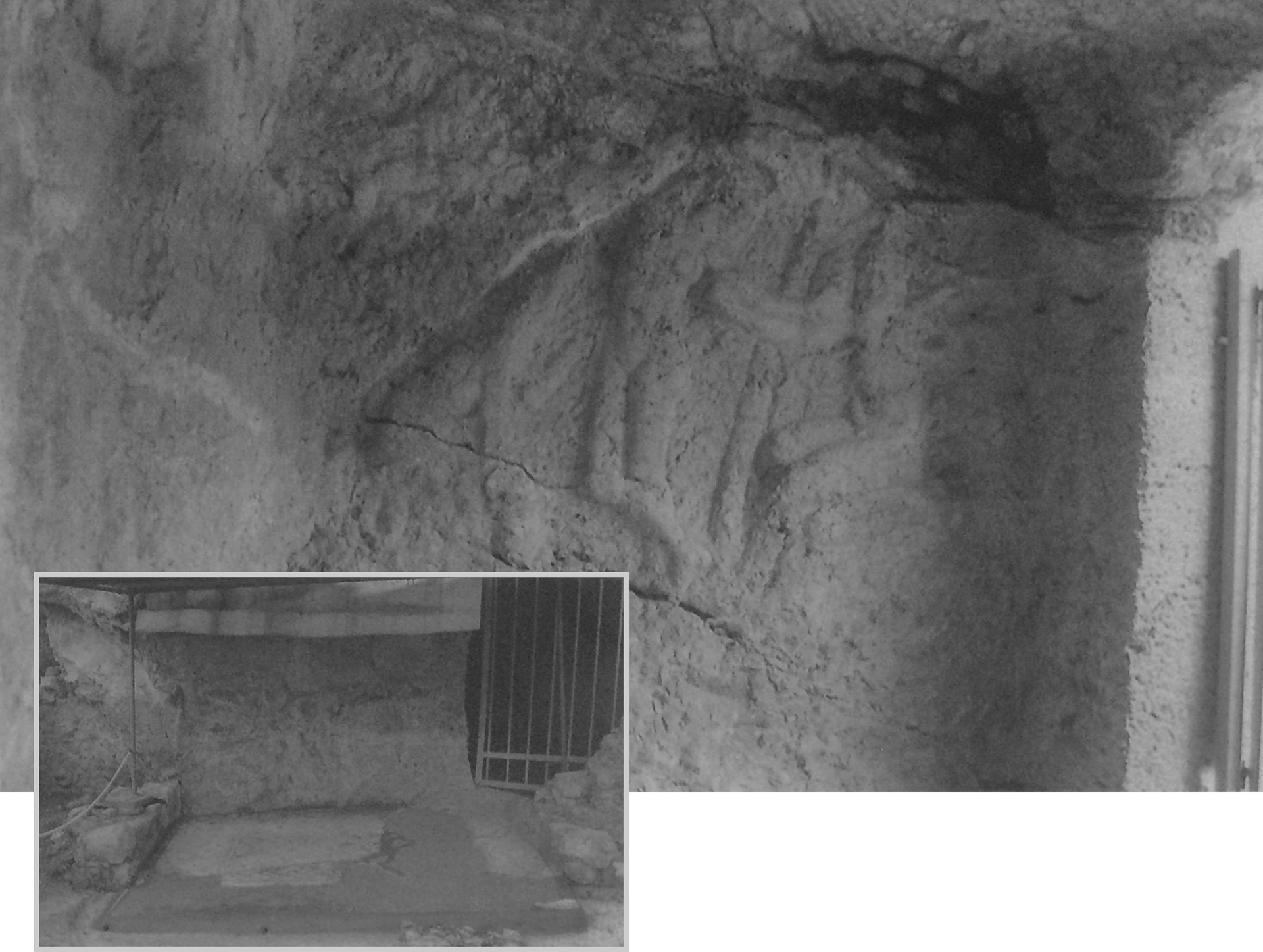

Detail from the interior of the chamber with the relief representation of Pan, a Maenad and a dog. Bottom: small room with the sanctuary of Pan preserving a mosaic floor and a mural.

(Source: Dakoura-Vogiatzoglou 2008, 251, fig. 5,6)

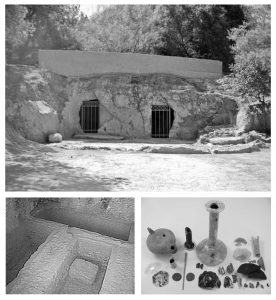

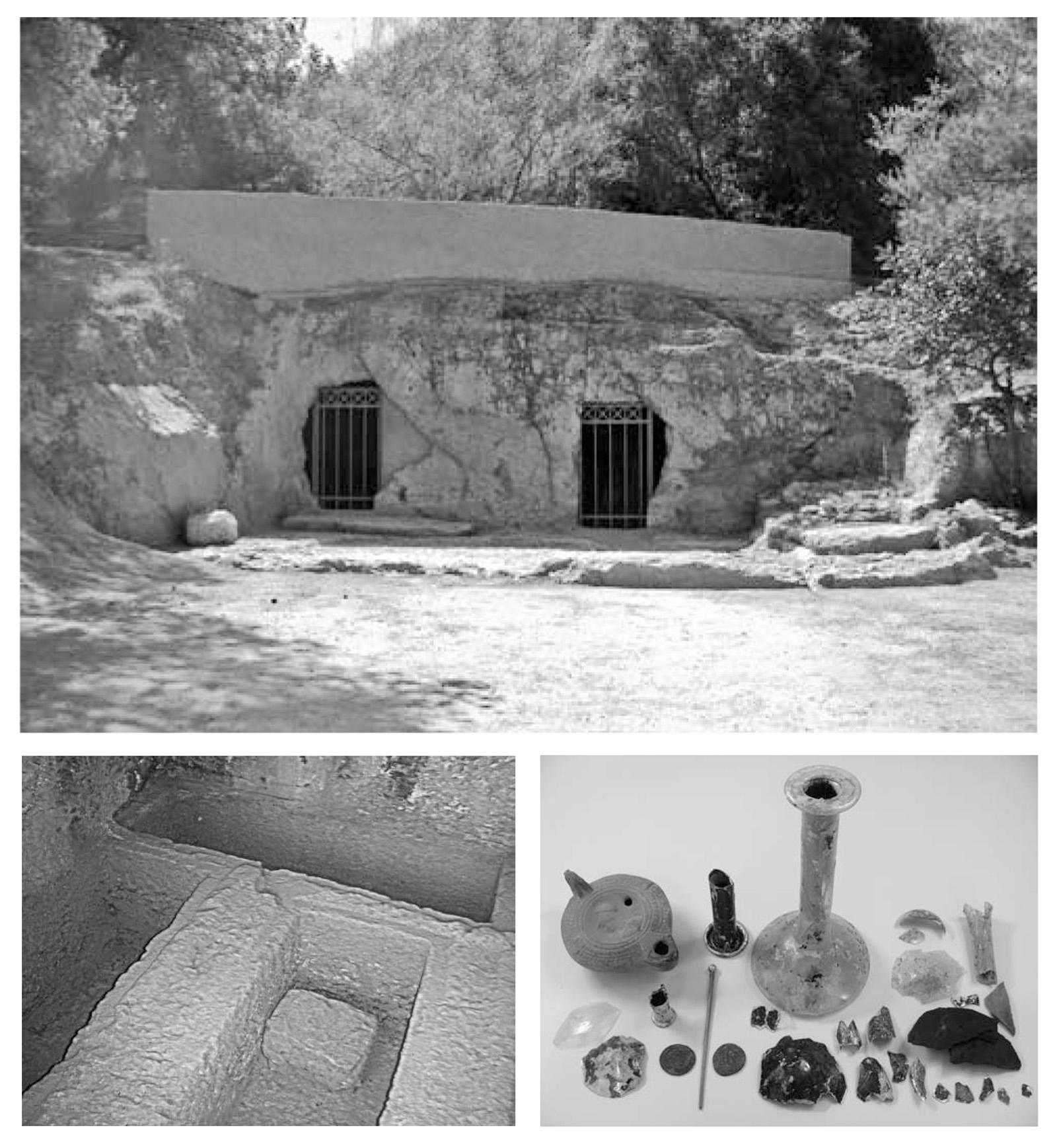

Early Christian period: Residential and funeral use of the Hills

It seems that the area of the Hills continued to be inhabited until the 6th century A.D., while the rock-cut caves near the Pnyx and the grounds of the Observatory suggest that the land served for burial purposes. In the meantime, the Hills maintained their strategic role, and the old fortification was repaired and reinforced by the erection of at least 15 towers. As the city of Athens diminished in size during the end of the Early Christian period, the Hills’ region goes once more desolate.

Selected bibliography:

Thompson and Scranton 1943, 372–376; Dakoura-Vogiatzoglou 2013, 197.

The façade of the so-called “Deaf-man’s” cave, the graves cut in the chamber’s interior and the findings revealed from the excavation of a pyre.

(Source: Vogiatzoglou 2009, 27–28, fig. 23, 25, 26)

Mid-Byzantine period: Erection of churches atop ancient ruins

The Hills’ neighbourhood is revived. Agios Demetrios Loumbardiaris is built upon the ruins of an ancient tower of the Compartment Wall (diateichisma). The little church of Agia Marina is founded following the bedrock cutting of an ancient cistern in whose inner wall frescoes of the 13th century A.D. are preserved. The desolate “Royal wall”, mentioned in the Praktikon of Athens –an official document of the Byzantine state–, is a landmark for the land properties across the edges of the city during the turn of the 12th century Α.D.; a section of this wall is in close proximity with the Koile district (village of Koile) and with the church of Agia Marina.

Selected bibliography:

Thompson and Scranton 1943, 376–378; Makri, Tsakos and Vavylopoulou–Charitonidou 1987–1988; Bouras 2010, 60–61.

The little church of Agia Marina wedged into the rock of the Hill of the Nymphs before its subsequent reconstruction. Sketch from 1853.

(Source: Royal Danish Library – Danish National Art Library, Harald Conrad Position, Inv. No. 17700)

Post-Byzantine period: Folk beliefs around the caves and the rock-cut spaces of the Hills

On this barren landscape lacking any form of vegetation, the natural caves and ancient rocky cuttings inspire stories in which history mingles with legends, while superstitions and folklore take shape. According to medieval tradition, the cave of the “Evil Sisters”, near the ancient Barathron was haunted by the sisters named “Plague”, “Cholera” and “Smallpox”.

Selected bibliography:

Dodwell 1819, 396; Kampouroglou 1922, 26–27; Dakoura-Vogiatzoglou 2009.

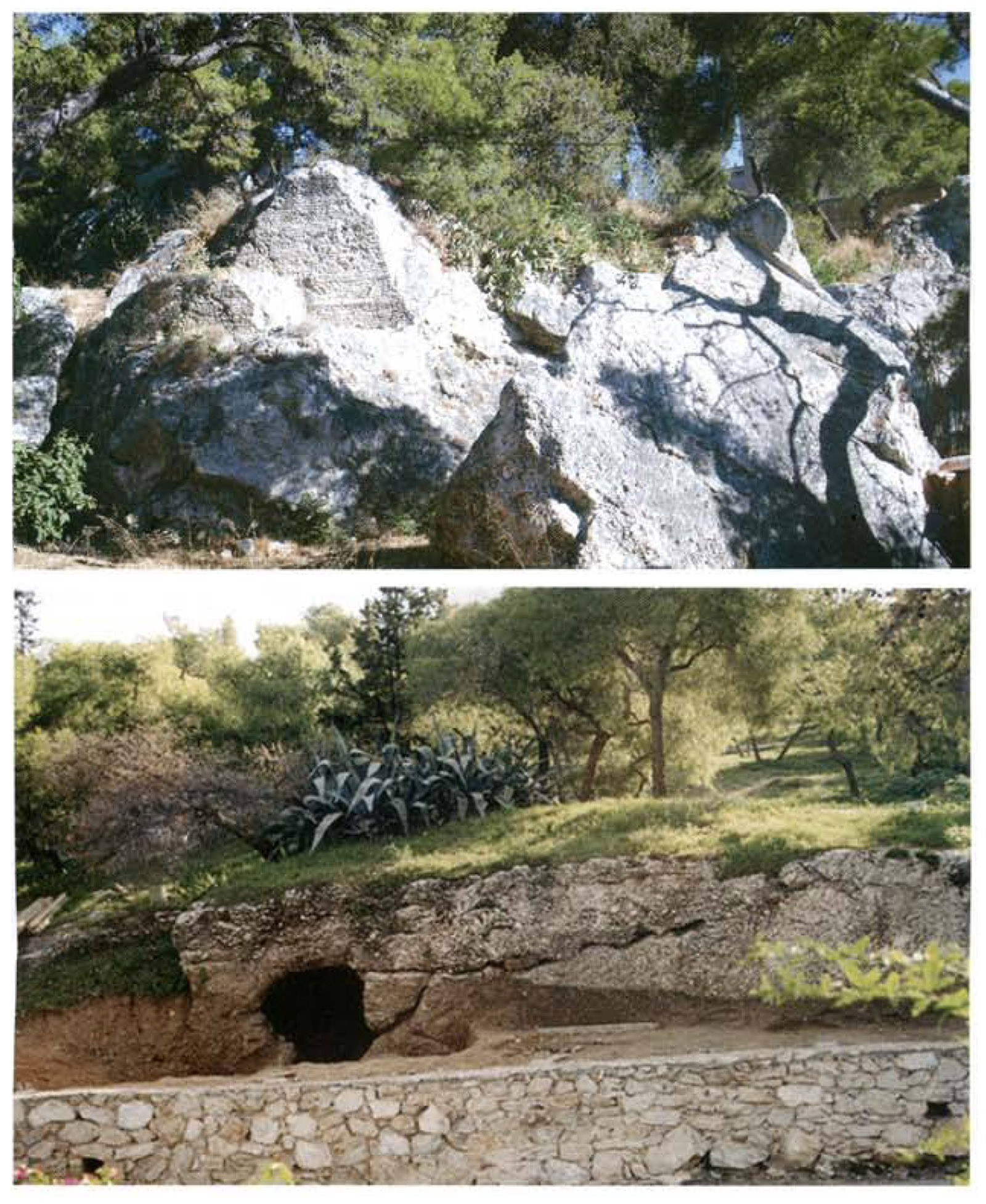

Top: Representation of the “Evil Mother-in-law” rock, upon the Hill of the Nymphs, where, the legend says, resided the “Moirai” and the “Fine Ladies”.

Bottom: The cave of the “Evil Sisters”. Photographs by Olga Dakoura-Vogiatzoglou.

(Source: Dakoura-Vogiatzoglou 2009, 10–11)

The Venetian–Turkish War: The siege of the Parthenon viewed from the Hills

According to sources, in 1687 the Venetians placed a battery of 15 cannons on the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos), another one of 9 cannons on the Pnyx and 5 huge mortars on the Hill of Areopagus, and directed them against the Castle. The Parthenon, the finest edifice of Classical art, suffered irreparable damage by the explosion.

Selected bibliography:

Hadjiaslani 1996.

Drawing representation of the Parthenon’s explosion in 1687 caused by the cannons of the Venetian commander, Morosini. Drawing in ink, ca. 1700–1770.

(Source: Royal Danish Library – Danish National Art Library, Frederik the Fifth Atlas, Bd. 46, Tvl. 39)

The siege of the Acropolis

The caves and fortresses of the Hills change hands between the Greek and Turk besiegers of the Castle, who were setting up their bastions on Agia Marina, on Seggio (Philopappos) and the Pnyx. The Philopappos Hill plays a significant role to the supply operations, like in October 1826, when 450 men of captain Kriezotis put into rout the few Turks guarding the Hill, until they were able to make their way to the Acropolis safe and sound in order to help the besieged.

Selected bibliography:

Sourmelis 2011 [1834], 227; Vlachogiannis 1901, 32–222.

A battle scene during the Greek Revolution, south of the Acropolis. One of the many paintings by Panayiotis Zographos painted under the guidance of Makriyiannis (1836–1839).

(Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Poliorkia_ton_athinon_kata_to_1827.jpg)

The first archaeological research undertaken by Pittakis

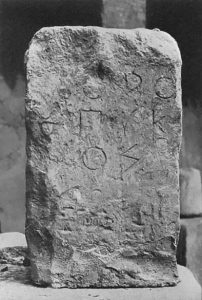

From 1831 onwards, and under the auspices of the Archaeological Society at Athens, the archaeologist Kyriakos Pittakis would now and then undertake searches in the area of the Pnyx. These brought to light a great number of inscriptions, the most important of them being a horos stone delimiting the public space in the area of the Pnyx (IG I3 1092). Thanks to Pittakis’ discovery the identification of the Hill with the spot of the Assembly Place is also attested by epigraphical evidence.

Selected bibliography:

Rangavis 1842–1843, 174; Pittakis 1852, 683, nos. 1134–1137; Pittakis 1853, 774, no. 1290; Petrakos 1987, 29; Peppas-Delmousou 1996.

The inscription IG I3 1092.

(Source: Kourouniotes and Thompson 1932, 108, fig. 7)

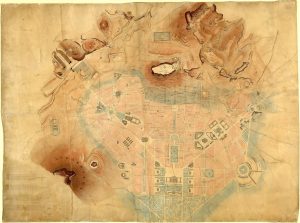

The Western Hills set outside urban planning

After the proclamation of Athens as capital of the newly-founded Greek state, the urban planning by architects Kleanthis and Schaubert keeps intact the ancient landscape of Athens on the Hills. The expansion of the city towards the North across a flat ground, as well as to the area among the Acropolis and Lycavettos, is deemed as the optimal land management of the new capital instead of a “city on hills” or “Otto’s city” as it was envisaged by Karl Friedrich, Schinkel, Ferdinand von Quat and Leo von Klenze. However, following the auctioning of stones from the Haseki wall (1778) during the first months of 1835 for procuring construction material for the new capital, the attention shifts to the rocky elevations to the west of Athens.

Selected bibliography:

Biris 1966, 38, 70–72; Papageorgiou-Venetas 2001, 120; Korres 2010, 18–21.

The urban design proposed by Kleanthis and Schaubert, featuring large squares, gardens and boulevards (1833).

(Source: Photographic Archive of the German Archaeological Institute at Athens, neg. D-DAI-ATH-Athen-Varia-0983_3315618.jpg)

Installation of the first abattoir

In a remote stretch of land to the north of the Observatory the first basic abattoir is established under the mayoralty of Demetrios Kallifronas (1837, 1840–1841). In his treatise on the Western Hills of Athens, the French Émile Burnouf makes mention of two abattoirs in 1849: the small one, to the northwest of the Observatory and the big one to the northern side of the ancient Barathron. During those years, as Kostas Biris characteristically writes, “the slaughtering of animals was taking place on the pavements, in front of the butcheries or anywhere else the butchers fancied”. In 1856, the mayor Konstantinos Galatis makes an effort to resolve the problem by ordering the construction of an abattoir on the riverbed of Ilissos, to the south of Philopappos. The abattoirs will remain there approximately until 1916 and then are relocated to the area of Tavros, during the mayoralty of Emmanouil Benakis.

Selected bibliography:

Burnouf 1856, 64–88; Biris 1966, 88.

The entrance to the abattoirs in Tavros. The erection of the slaughterhouses in the area was of such importance that the settlement formed there obtained the name “Nea Sfageia” (New Slaughterhouses), and later, in 1936, it was renamed as “Tavros”.

(Source: Dipylon)

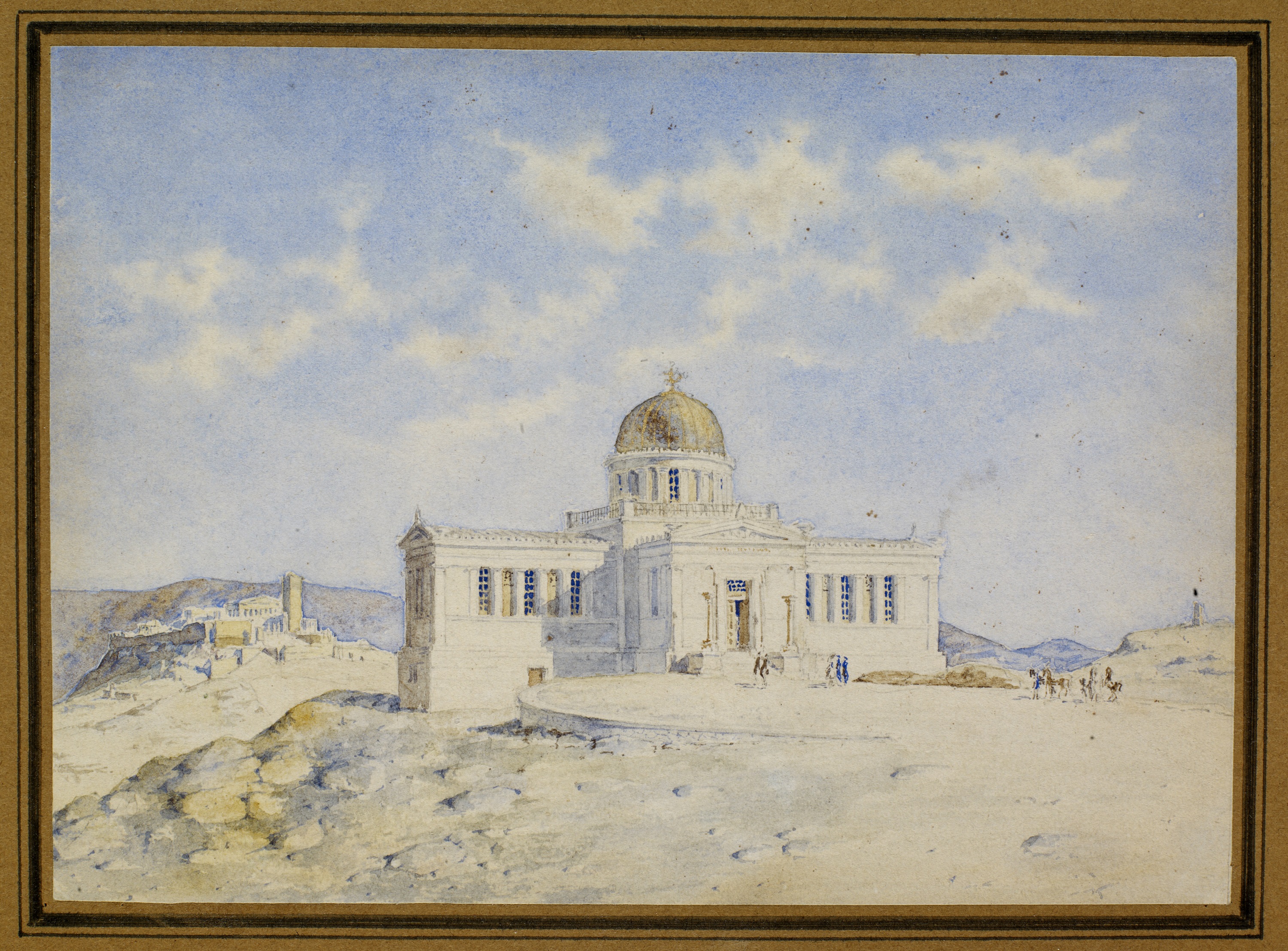

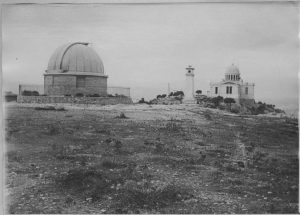

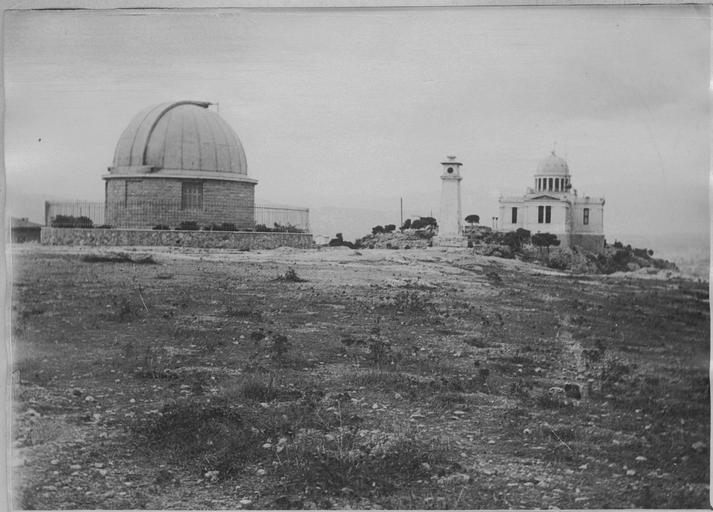

The construction of the Observatory and excavations at the rear of the Pnyx

The first research foundation in Greece was housed in a building constructed upon drawings of the Danish architect Theophilus Hansen, and thanks to a donation by the baron Georgios Sinas, consul of Greece in Vienna. It was chosen to be built on the Hill of the Nymphs –contrary to the initial proposal which was the Hill of Lycavettos– and this choice may be related with ancient testimonials mentioning that during the 5th century B.C. the Athenian astronomer Meton made his observations from this very spot. The year the Observatory was erected, the Archaeological Society at Athens once more excavates “at the rear of the Pnyx”, as the Society’s secretary, Alexandros Rizos Rangavis, announces, “a cave coated with mortar, bearing traces of blue dye.”

Selected bibliography:

Rangavis 1842–1843, 174; Biris 1966, 130–131; Petrakos 1987, 29; Zerefos et. al. 2013, 32–34.

The façade of the Observatory of Athens, the Acropolis on the left at the far end and the monument of Philopappos on the right. Watercolour by Theophilus Hansen (1842).

(Source: Royal Danish Library – Danish National Art Library, Collection: Architectural Drawings, Hansen, Theophilus, Inv. No. 16915)

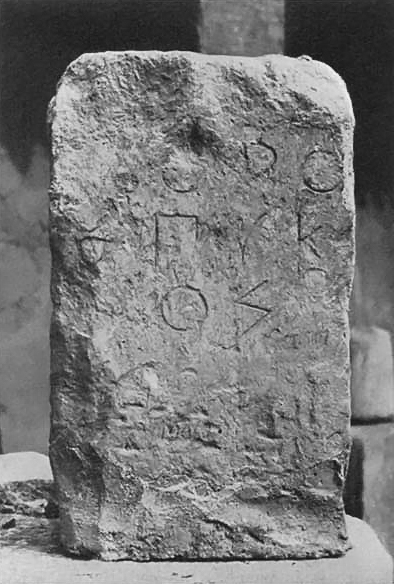

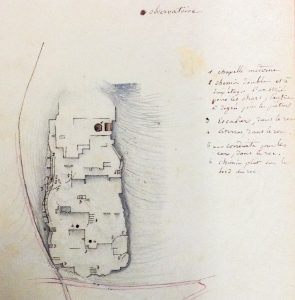

The archaeological map by Émile Burnouf

In his treatise, Émile Burnouf, a delegate of the French School of Archaeology, describes and depicts on an accompanying map the ancient remains of houses, streets, cisterns and graves that were visible across the area before the quarries’ expansion. The map by Burnouf constitutes compelling evidence of the ancient character of the rocks and therefore becomes an important tool in the hands of Panagiotis Efstratiadis, General Ephor of Antiquities. The latter puts in an Herculean effort striving to convince those in charge to take action against quarrying in order to avert the destruction of unique historical evidence pertinent to the settlement of the Hills.

Selected bibliography:

Burnouf 1856, 64–88.

Sketch by Émile Burnouf; plan of the cuttings at the plateau of Agia Marina.

(Source: Université de Lorraine / Direction de la Documentation)

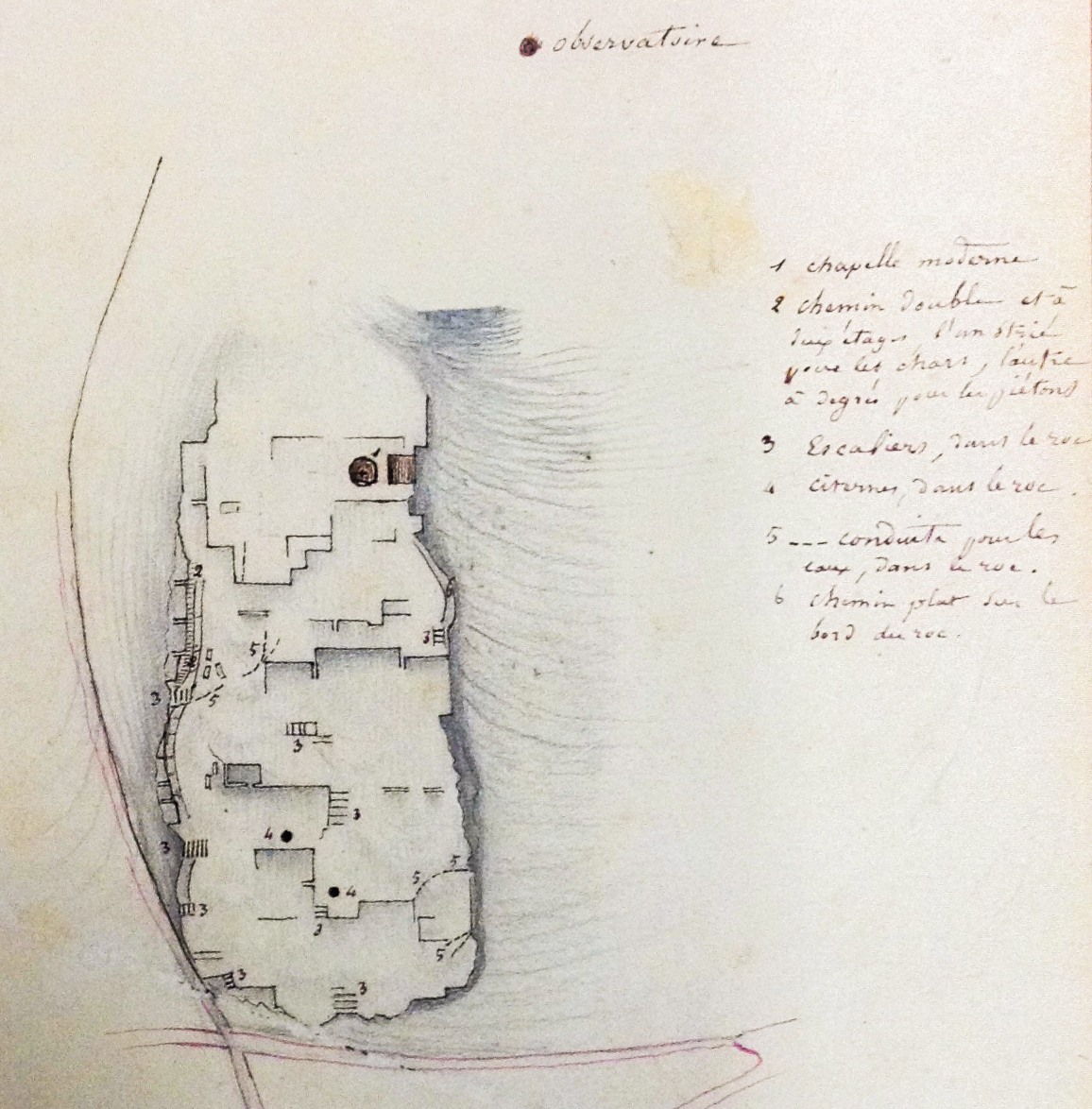

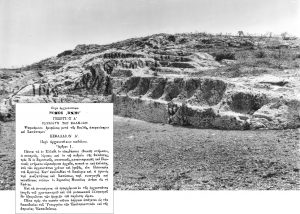

The excavations on the Pnyx and the Act on the deregulation of quarrying

The Archaeological Society at Athens undertakes excavations under the direction of Petros Pervanoglou, west of the Hills of the Pnyx and of the Muses (Philopappos). The works last 40 days and bring into light more than 100 graves. At the same time, the Act 690/1861 (Art. 41) is adopted, allowing for the unrestricted operation of quarries outside the inhabited area of the city, which intensified the commercial exploitation of the quarried product on the rocky grounds of Athens, such as Lycavettos, the three Western Hills, Kolonos Hippios and the hill of Strefi. Almost every effort on the part of Efstratiadis, the General Ephorate of Antiquities, to control the quarries proves unfruitful. The judicial authorities favour repeatedly the quarriers because the locations from which the sought-after stones are being extracted remain private properties.

Selected bibliography:

Pervanoglou 1862; Petrakos 1987, 43; Calligas 1996, 1–5; Theocharaki, Costaki and Papaefthymiou 2018, 309–319.

The Act 690/1861 was the triggering cause for the rampant quarrying at the Western Hills of Athens, which compromised the antiquities’ safety.

(Source: G.G. 690/1861)

The first systematic attempt to map the antiquities

In 1878, archaeologist and historian Ernst Curtius, and cartographer and topographer Johann August Kaupert undertook a systematic mapping of the antiquities in the region of the Western Hills. As it is mentioned in the explanatory notes accompanying the project Atlas von Athen (Atlas of Athens), “these traces of ancient life disappear year after year as a result of the reckless exploitation of the Western Hills of Athens that are being relentlessly looted and blasted, and crumble to piles of ruins.”

Selected bibliography:

Curtius and Kaupert 1878; Korres 2008.

Atlas von Athen

(Source: Curtius and Kaupert 1878, Bl. VI)

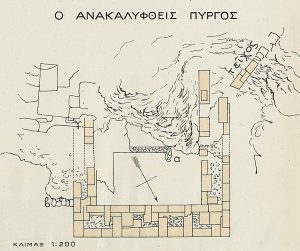

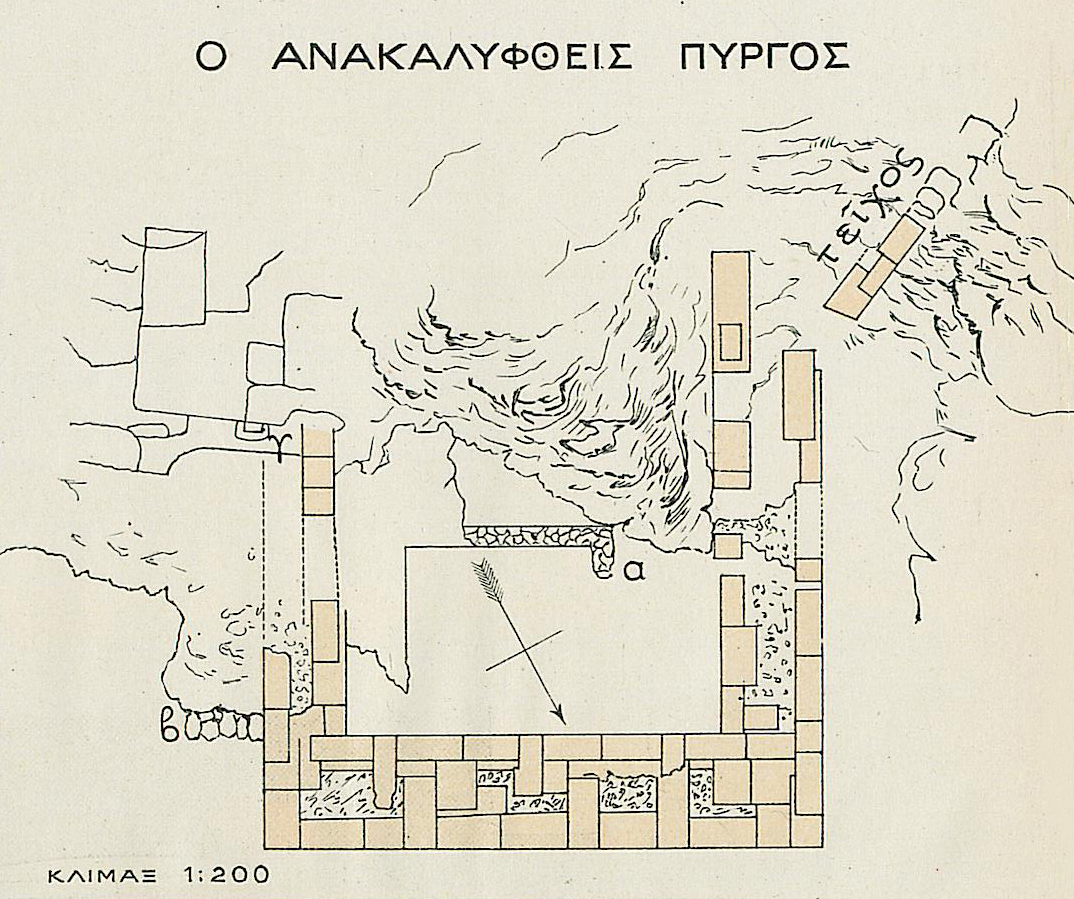

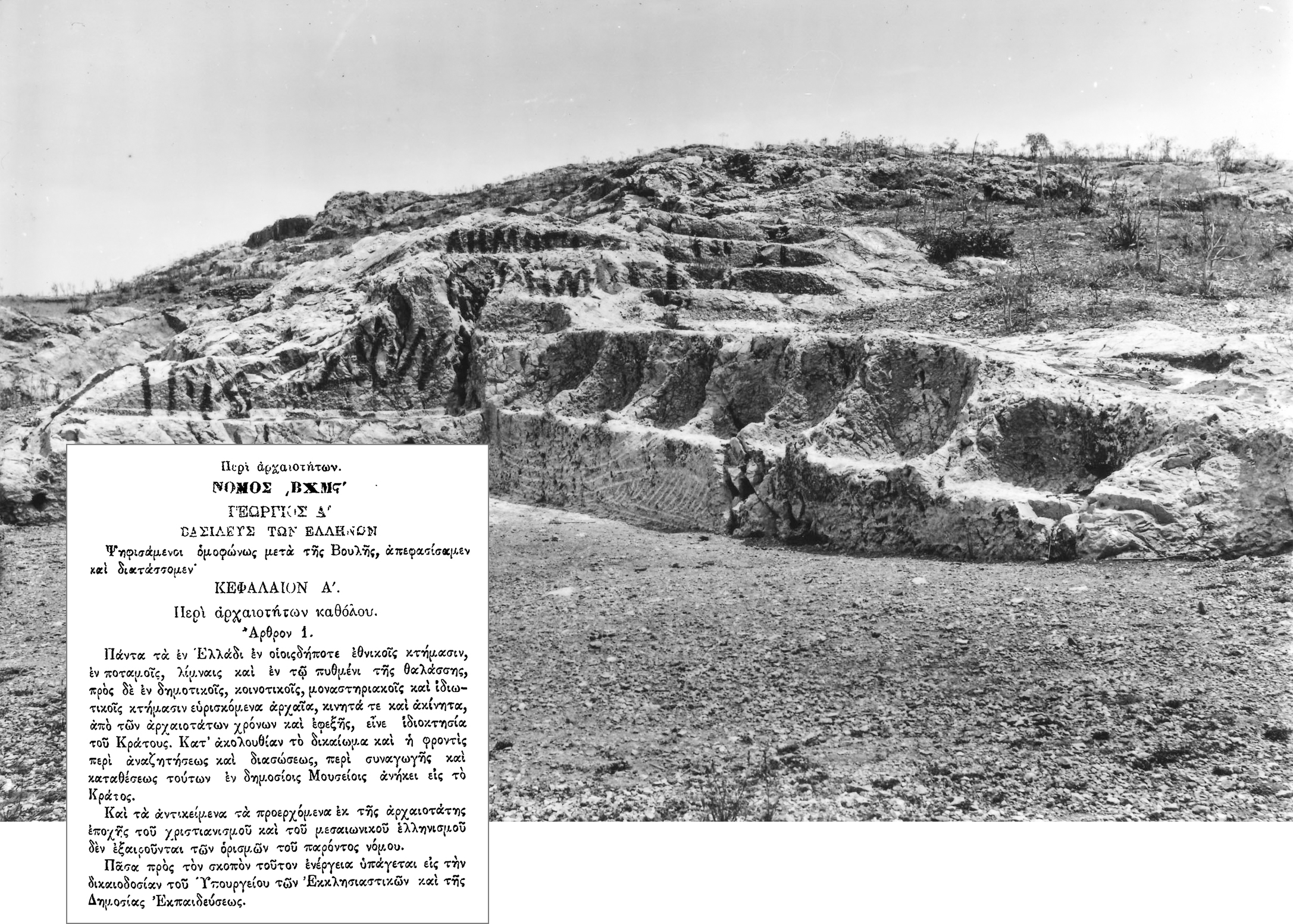

Excavations at the top of the Hill of the Muses and next to the Observatory

The summit of the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos) is excavated under the supervision of Andreas Skias, the objective being to find the architectural elements of the monument of Philopappos and to determine its design. During the roadway opening for the transportation of stones from the quarry of the area, a large square tower of the Macedonian fortress comes into a light. In the same year, an excavation by the Observatory, supervised by Georgios Sotiriadis, exposes many cremations, but also drain pipes from earlier settlements, clay moulds and thirteen inscribed funerary kioniskoi.

Selected bibliography:

Skias 1898, 70–71; Travlos 1960, 80, 122.

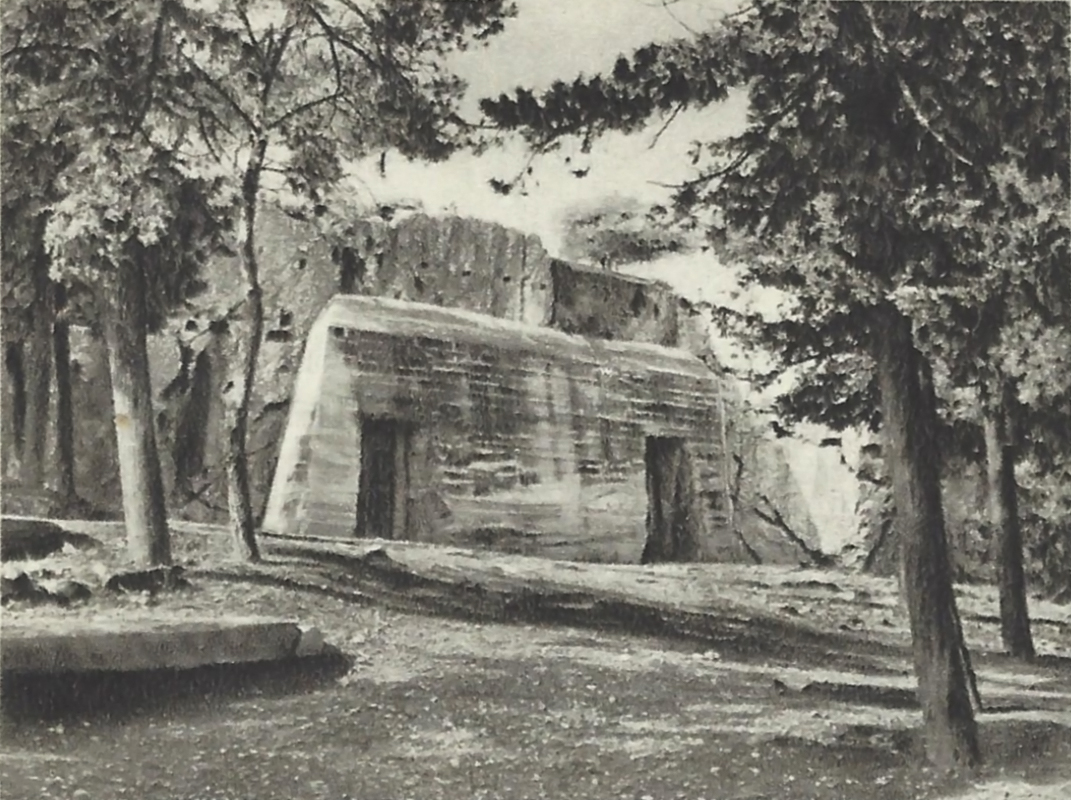

A drawing of the fortification tower that was discovered during an excavation in 1898, on the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos). The tower was part of the Macedonian fortress that was built in 294 B.C. when Demetrios Poliorketes was in charge of the city.

(Source: Skias 1898, pl. 1)

New proprietorship of the rocky heights

The status of the quarries changes definitively by the Act 2646/1899 “On antiquities”, according to which the proprietorship of the rocky heights bearing ancient structures and cuttings come definitively under the authority of the public sector, whereas quarrying and the operation of lime kilns are prohibited in a radius of 300 metres from the antiquities. Notwithstanding the prohibition, the quarries continue their operation in the region of the Western Hills. The Archaeological Service denounces by name quarrymen and land-grabbers, and succeeds in gradually closing down the remaining quarries. From 1923 onwards, quarrying is prohibited on the Havara rock in Petralona, as well as on the whole rocky formation to the northwest of the Hill of the Pnyx, all the way to the flume of the ancient Koile.

Selected bibliography:

Biris 1966, 70–72; Dakoura-Vogiatzoglou 2013, 204.

Graffiti on the ancient rocks around the so-called Eptathronon. The word “ΔΗΜΟΣΙΟΝ” [i.e. PUBLIC] certifies the new proprietorship of the rocks, averting the quarrymen from any illegal activities.

(Source: G.G. A 158/1899 & Nicholson Museum, curator William J. Woodhouse, Greece, NM2007.59.10)

The gradual afforestation of the Hills

The Philodasiki Enosis (Society of Friends of the Forest) is founded in 1899 and undertakes to carry out the important project of reforesting the basin of Attica. After the introduction of Act 2740/1900, the project expands. Hence, after the decision to suspend the operation of the quarries, the tree planting of some cypresses and many pines commences on the Hills of the Muses (Philopappos), the Nymphs and the Pnyx.

Selected bibliography:

Biris 1966, 271–273; Dakoura-Vogiatzoglou 2013, 204.

The Hill and the monument of Philopappos shown on photographs taken from the Acropolis. A comparison of the contemporary photograph with that of 1905 reveals the immense change that took place on the Hill after its afforestation, during the Interwar period.

(Source: Dipylon)

The installation of the radio communication system station

To the southwest of the Observatory the station of the radio communication system is installed, with a 45-metre long antenna. According to Manolis Korres, the location of the building is identified approximately with the junction of the modern Antoniadou and Aristagoras Streets. Later, in 1923, the building will house the Radio transmitting Faculty of the Greek Navy War School.

Selected bibliography:

Korres 2017, 200–201

The German radio communication system at the foot of the Hill of the Nymphs (a district later called “Asyrmatos”), 1917.

(Source: Ministère de la Culture (France) – Médiathèque de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine – Diffusion RMN, APOR129149)

The Doridis telescope

The large refracting telescope of the National Observatory of Athens is manufactured by the French house Gautier, financed by donations of Greeks of the Diaspora; it is installed under a special vault, a few metres away from the bema of the Pnyx. The telescope is available to this day for night sky observation of the planets and celestial phenomena.

Selected bibliography:

Zerefos et. al. 2013, 79; Visitor Center in Thissio.

Atlas von Athen

(Source: Curtius and Kaupert 1878, Bl. VI)

Excavations on the Pnyx

Under the supervision of Konstantinos Kourouniotes, the Archaeological Society at Athens undertakes excavations in order to study the monumental retaining wall, and it is confirmed that the area is identified with the ancient Pnyx, the Assembly Place of the people.

Selected bibliography:

Petrakos 1987, 111, 117; Calligas 1996, 1–5.

The 9-courses high preserved retaining wall, of an earlier date than the retaining wall of the 3rd building phase of the Pnyx (1910).

(Source: Kourouniotes 1910, 130, fig. 2)

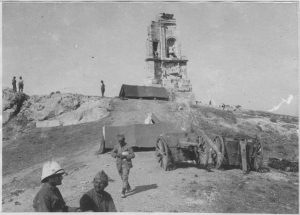

The “Allied Army of the Orient” camps on the Hill of the Muses

Despite the initial neutrality of Greece in World War I, in October 1915 the Anglo-French army of Entente lands in Thessaloniki and forms the “Allied Army of the Orient”. Soon, Greece is officially divided into the Government of Athens under H. M. King Constantine and into the Provisional Government under the leadership of Eleftherios Venizelos, a fervent advocate of the Allies. On 18th November 2016, the allied troops land at Piraeus, march to Athens and camp, among other places, on the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos). The “National Schism” culminates in 1916, after a conflict that became known as “Noemvriana” (November events). In 1917, the lens of the Photographic Services of the Allied Army of the Orient captured Athens at that time, bequeathing to future historians a significant heritage.

Selected bibliography:

The Sphere newspaper, London 16 Dec. 1916; Mourelos 2007.

The monument of Philopappos witnesses the daily routine of the “Allied Army of the Orient” (1917).

(Source: Ministère de la Culture (France) – Médiathèque de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine – Diffusion RMN, APOR119802)

The district of “Asyrmatos”

In the area close to the radio transmitter of the Greek Navy War School and on the rocks of the old quarry on the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos) settle 800 immigrant families from Asia Minor who use meagre means, such as sheets of steel and planks, to secure provisional shelter, and live under appalling conditions. In 1923, the Ministry of Agriculture hands over to the National Council of Greek Women the all-green grounds that today are known as Konistra, intended to be used by children of the refugee district. The area assumes the name “Attaliotika” or “Asyrmatos”. In 1961, the quarter is used as the natural setting for the shooting of the Greek film A Neighbourhood Named the Dream (Synoikia to oneiro), one of the most important films of Greek cinematography, directed by Alekos Alexandrakis. The film wreaks havoc and is screened amidst reactions on account of its realistic images showing the conditions of poverty and misery that existed in Athens. Finally and after protests by the Press, only its censored version is allowed for screening in cinema theatres of the urban centres exclusively.

Selected bibliography:

Vougiouka and Megaridis 2009, 63–72.

View from the refugee settlement of “Asyrmatos”, behind the church of Agion Asomaton. Petralona, 1920–1929.

(Source: ERT Photographic Archive)

The residence of the famous painter Parthenis

The controversial modern-style and example of the Bauhaus architecture residence of Constantinos Parthenis (1878–1967), one of the most prominent Greek painters of the 20th century, stands out on the junction of 40 Rovertou Galli and Dionysiou Areopagitou Streets, right beneath the Acropolis. Its erection in 1924 signals the first violation of the archaeological landscape at the eastern side of the Hills. The decision for demolishing the house is taken within the scope of the area’s reformation, a project which is however aborted when the painter threatens to blow himself up along with his paintings. Eventually, the house is demolished soon after his death.

Selected bibliography:

Biris 1966, 394; Eleftheria newspaper, 28/01/1967.

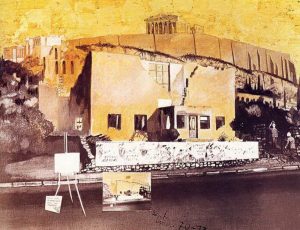

The residence–workshop of the painter Constantinos Parthenis on Dionysiou Areopagitou street is captured in a painting by Spyros Vassiliou, entitled “A Tribute Visit to the Ruined House of Parthenis”, 1970–73.

(Source: The publication of the painting is approved by the official archive of the artist Spyros Vassiliou)

The construction of the new church of Agia Marina below the Observatory

The once-upon-a-time medieval, cave-like little church of Agia Marina is integrated into the reconstruction plan of a new and far larger church bearing the same name, based on drawings by Achilleas Georgiadis.

Selected bibliography:

Biris 1966, 394; Lalonde 2005, 92–93.

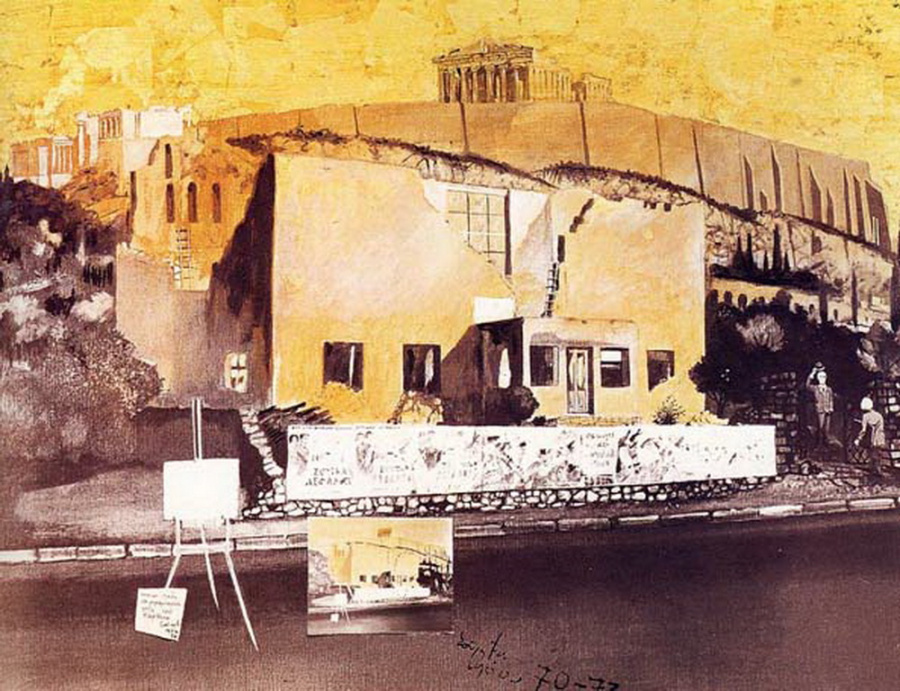

Amidst the dense vegetation of the Hill of the Nymphs stands out the contemporary church of Agia Marina; the Observatory of Athens can be seen behind it.

(Source: Reader.gr)

The Americans excavate the Compartment Wall (diateichisma)

In the years 1932–1937, the American School of Classical Studies undertakes excavations in collaboration with the Archaeological Service. During the period 1936–1937, the whole, 850-meters-long Compartment Wall is restored at least on 70 excavation trenches.

Selected bibliography:

Thompson 1936, 151–200; Thompson and Scranton 1943, 269–383.

Semi-circular tower from the early 2nd century B.C. that reinforced the Compartment Wall on the Hill of the Pnyx. It was brought into light in 1943, after the excavation undertaken by the American School of Classical Studies.

(Source: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives, Archaeological Photographic Collection, AP 0525)

The “Bastias Theatre” disrupts the ancient landscape

During Metaxas’ dictatorship, works commence for the construction of an outdoor theatre between the western slopes of the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos) and the Hill of the Pnyx, next to the ancient Koile road. The project remains unfinished due to its enormous cost, the archaeologists’ reaction in view of the damage inflicted on the ancient landscape of the Hills and because of the subsequent outbreak of the war in 1940.

Selected bibliography:

Biris 1966, 330–331, 394–397; Dakoura-Vogiatzoglou 2004, 7.

Part of the 1944 aerial photograph; the whole plan of the Bastias theatre is still visible, before the works for enhancing the archaeological site during the 1990s.

(Source: BSA Aerial Photographs, frame No. U37/3275-3285)

The commonly called “Prison of Socrates” becomes a hideaway for antiquities

In view of the imminent national threat, on the eve of the Occupation of Greece (1940–1941) and soon after Greece entered World War II, archaeologists use this spacious construction cut on the rocky slope of the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos) as a safe place for hiding and protecting antiquities of the National Archaeological Museum.

Selected bibliography:

Papaspyridi-Karouzou 1946, 1158–1163; Kokkou 1977, 143–144.

During World War II, the so-called “Prison of Socrates” is supported by reinforced concrete in order to host and keep safe a great number of antiquities that were endangered either by bombings or pillaging. Photograph S. Meletzi.

(Source: Miliadis, n.d., fig. 101).

The district of “Asyrmatos” amidst the tumultuous Greek Civil War

During the “Dekemvriana” (December events), the district of “Asyrmatos” becames scene of conflict between the two combating forces. ELAS is the absolute dominant power in the neighbourhood of Petralona, whereas Thiseion is the place of action of the Organisation X, led by Georgios Grivas. It is a violent clash, leaving part of the district in rubbles. The Hill of the Muses (Philopappos) also becomes battleground. Sometime later, in the first post-war decade, the facilities of the Greek Navy are withdrawn from Ano Petralona and a complex of school buildings is constructed in the area of “Asyrmatos”.

Selected bibliography:

Vougiouka and Megaridis 2009, 59–62, 70.

Queen Frederica’s “Stone Houses”

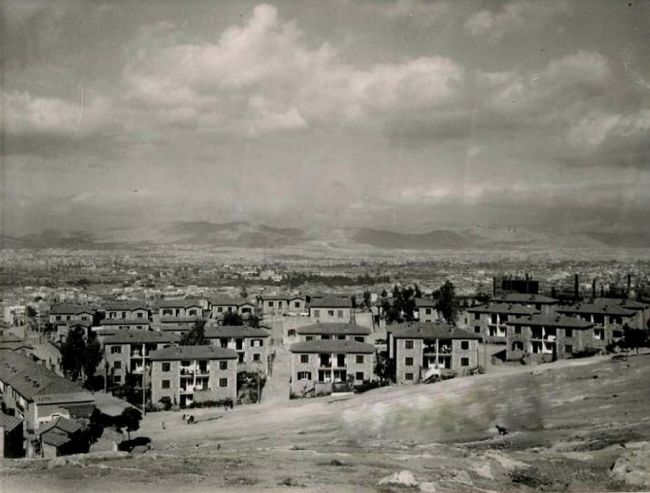

After the destruction of the district of “Asyrmatos” in 1944 and following an initiative by Queen Frederica, it is decided to build a new settlement by means of a fundraising by the “Royal Welfare Fund”, comprising stone-built houses, some of which are still preserved. The official name of the settlement was “Perikleous”. The elaborate, dressed stones from the Greek Navy War School are used for the construction of the houses.

Selected bibliography:

Biris 1966, 397.

The residential quarter “Perikleous” that is commonly known as “Frederica’s stone houses”. These buildings maintained the typical style of refugee dwellings –a ground-floor building of two semi-detached houses– and housed dozens refugees after the district of “Asyrmatos” was destroyed. Quite a few of them are still standing to this day.

Illicit quarrying at “Skalakia”

The ancient rock-cuttings south to the ancient Koile road are being intensely quarried, at least between the years 1938 and 1944, the year when the aerial photograph was taken. The quarry belongs to Konstantellos family and in 1954 resumes its operation for one year. The deep hollow left by quarrying is immediately proclaimed as archaeological site; today it is covered by soil and thin vegetation.

Selected bibliography:

Dakoura-Vogiatzoglou 2013, 204.

A 1944 aerial photograph, on which the area around the Konstantellos quarry and the location “Skalakia” is designated by a circular sign.

(Source: BSA Aerial photographs, frame No. U37/3275-3285 & Nicholson Museum, curator: William J., Woodhouse, Greece, NM2007.123.12)

The first systematic attempt to map the antiquities

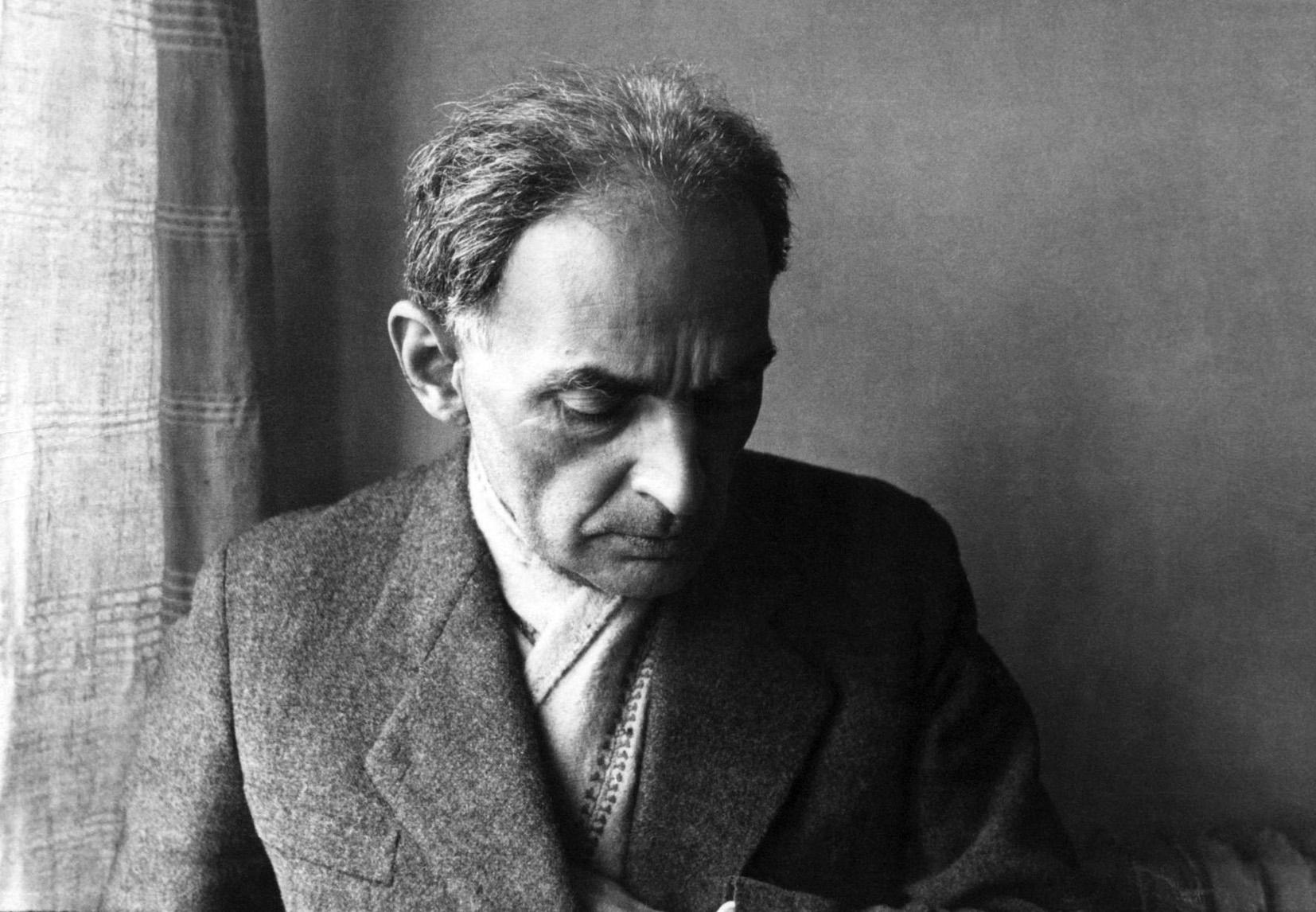

The great architect and writer Dimitris Pikionis (1887–1968) arranges with unequalled craftsmanship the region around Acropolis, connecting it to the Hills of the Muses (Philopappos) and the Pnyx with cobblestoned streets, pathways and resting benches, placed at carefully chosen spots. Pikionis realised the idea of a Resting Place for “introspection and clairaudience”, next to the church of Agios Dimitrios Loumbardiaris, that eventually operates for a number of years as canteen.

Selected bibliography:

Papageorgiou-Venetas 2004, 93–107; Pikionis 2017.

Photograph of Dimitris Pikionis taken by Pavlos Mylonas.

(Source: Lifo)

The construction of the restaurant “Dionysos”

It is built on the slopes east of the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos) and opposite the Acropolis by the architect P. Vassiliadis. As Kostas Biris writes about the building, “… since then [it] has been shamelessly gazing at the Parthenon”. The painter Yiannis Moralis undertakes the interior and exterior design.

Selected bibliography:

Biris 1966, 397.

The aforementioned quotation taken from Biris’ book.

The outdoor theatre of Greek Dances “Dora Stratou”

The theatre is located at the foot of the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos) and its seating capacity is 900 persons. It bears the name of the outstanding Greek actress and choreographer who contributed to the preservation of Greek folk music and traditional dances.

Selected bibliography:

Greek Dances Theatre “Dora Stratou”.

A dance show at the outdoor theatre “Dora Stratou”. The theatre’s permanent stage set was supervised by the famous painter Spyros Vassiliou.

(Source: ιστότοπος)

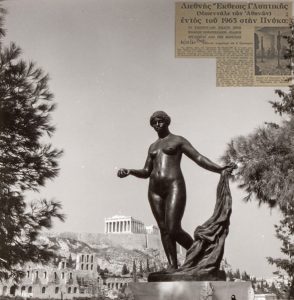

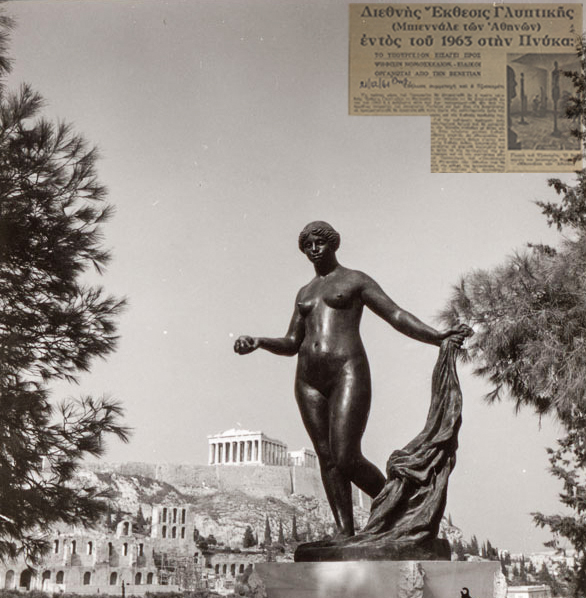

Exhibition “Panathenea of Contemporary Sculpture”

Within the scope of the Athens Festival, an exhibition of modern large-scale sculpture is organised for the first time, up to the standards of a biennale. Works by significant artists, such as Dali, Matisse and Picasso, are exhibited at the outdoor space of the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos).

Selected bibliography:

Eleftheria newspaper, 21/12/1961; GNTO (Greek National Tourism Organisation) 1965; Adamopoulou 2004, 249–250.

A photograph of Auguste Renoir’s “Venus Victrix”. The piece of sculpture was among the exhibits at the International Exhibition of Sculpture (Athens Biennale) that took place in 1965 on the Hill of the Muses (Philopappos).

Article from the newspaper Eleftheria (top right), making mention of the special event of the International Exhibition and of the internationally acclaimed artists that would participate.

(Source: Archive of Tonis Spiteris. Teloglion Fine Arts Foundation, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki)

The “Large Block Apartment”

This block of flats is constructed in order to cover the housing needs which had not been fully met by the “Stone houses” after the 1944 fire that broke out at the district of “Asyrmatos”. At the same time, the construction of the ring road of Philopappos is completed, while the Hill of the Nymphs enters the list of “historical places and landscapes of exceptional natural beauty.”

Selected bibliography:

G.G. 606/B3-10-1967 Act on the declaration of historical preserved places.

The block of flats “Asyrmatos”, as it is called nowadays, on the Philopappos ring road, was designed by architect Elli Vatikioti. The five-storey building consists of 55 apartments and 8 shops.

(Source: Dipylon)

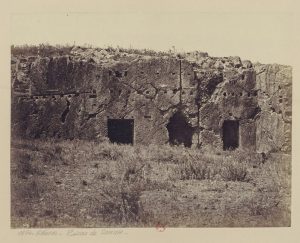

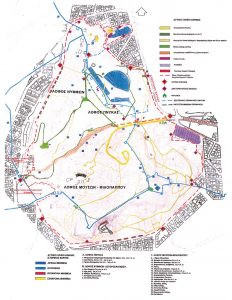

The incorporation of the Hills into the works for the Unification of Archaeological Sites

The “Bastias Theatre” is demolished and works are under way for enhancing the archaeological landscape, such as the restoration of the ancient Koile road, as well as excavations that led to newly-found antiquities. Τhanks to this major project a large, “open-air” museum is created; today an itinerary, appropriately adjusted for strolling, connects Dionysiou Areopagitou, Apostolou Pavlou and Ermou Streets, reaching as far as the Kerameikos Square. The “Grand Promenade” is “ad infinitum in the possession of the city”.

Selected bibliography:

Papageorgiou-Venetas 2004, 109–179.

The so-called “Grand Promenade” as envisaged by the study group of the construction company PLEIAS: Apostolou Pavlou Street. Left: the area of Melite. Right: the planted eastern slope of the Pnyx. A perspective drawing by Petros Zervos (2000).

(Source: Website of Pleias Ltd. Study group members: Dimitris Diamantopoulos, Orestis Viggopoulos, Katerina Ghiouleka, Anastasios Zervas, Claire Palyvou)

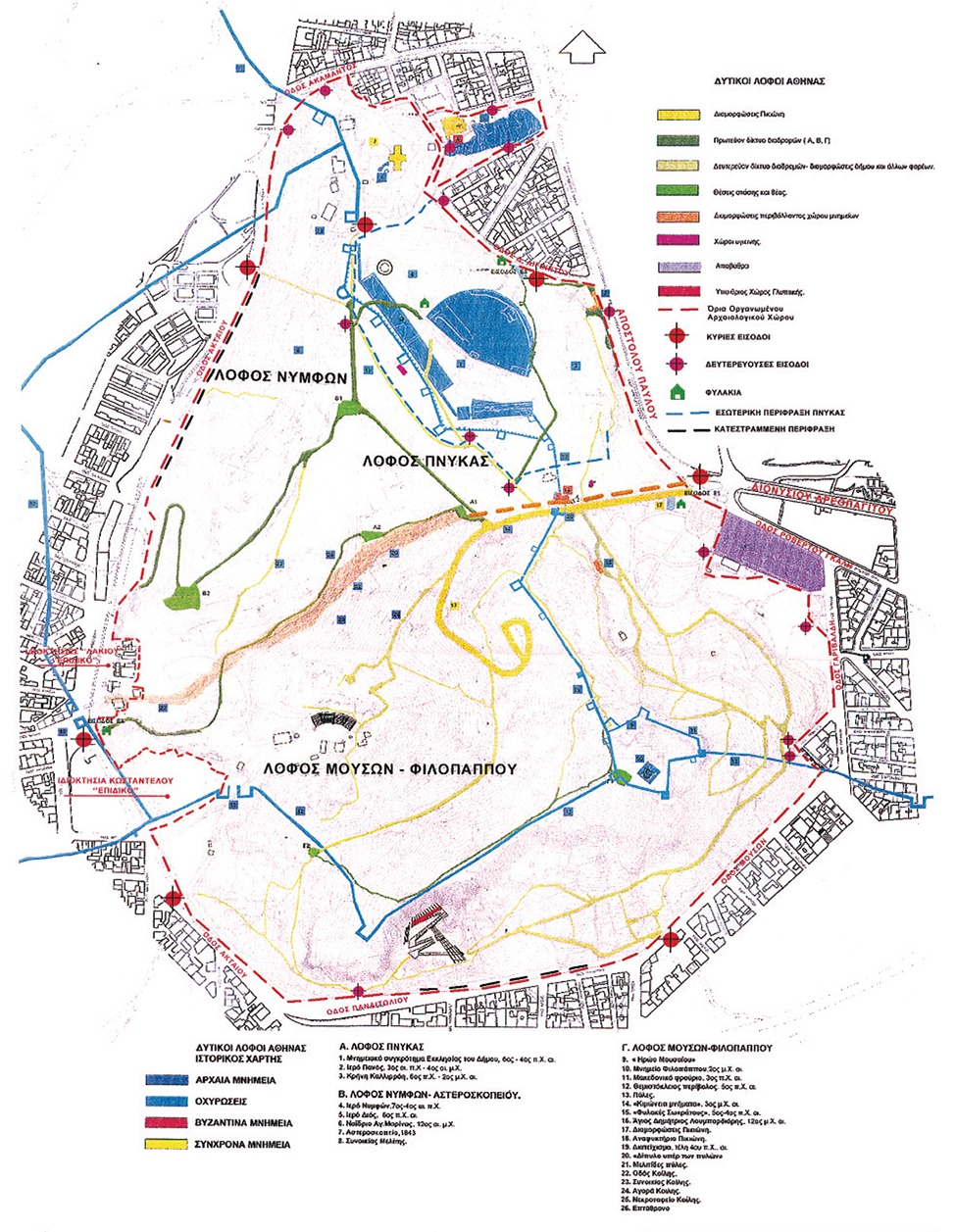

The Western Hills as an organised integrated archaeological site

With the aim to upgrade the aesthetic and cultural quality of the Athenians’ life, it is decided to keep the area open throughout the day and accessible without the need of a ticket to enter it. Signposts inform the public about the entrance points, itineraries inside the archaeological site are being planned, while the monuments located on the Hills are accordingly designated.

Selected bibliography:

Papageorgiou-Venetas 1994, 147–154.